This research paper aims to present, explain and order the elaborate and multilayered body of rituals, traditions, and symbols that regard luck and abundance in Indian culture.

From a macro perspective – based on history and religion – to a micro-positioning among an immense body of iconography, we will propose a simple yet careful systematic view of all that the Subcontinent considers to bring fortune (or misfortune) and prosperity, in a comprehensible manner, especially for the uninitiated outsider.

The presented lucky rituals, symbols, and medallions may not have an immediate application in betting, lottery, and casino gambling, especially in the context of online gaming. Yet, they reveal what interests, influences, and moves the average desi user when pursuing a lucky streak or hoping for a fortunate turn. This report should serve operators and vertical intermediaries to avoid crucial mistakes and position their platforms for style and imagery without crossing unwarranted boundaries.

Historical Significance of Cultural and Religious Symbols

The challenging task of compiling a systematic presentation of the innumerable auspicious symbols in present day Indian culture has, despite all, its cornerstones and basic assumptions. These foundations result from historical processes that have taken place in the land and are mostly consolidated around religious doctrines and established practical traditions.

In fact, India’s first Prime Minister and prominent independence activist, Jawaharlal Nehru, consistently promoted the “Unity in diversity” outlook for his compatriots. Traditions and beliefs crossing over between states and ethnic groups being prime examples of such heterogeneous unity.

It is, therefore, not a bold claim to make that these elements not only illustrate Indian culture but provide a strong bonding factor. The complex iconography, religious semiotics, and massive register of superstitions help create solid links between Hindus, other national religions, denominations, northerners and southerners, affluent citizens, and less fortunate ones. Traditions and symbolic manifestations maintain, most importantly, links between the past and the present, religion and secular life, and legitimize superstition as an important part of everyone’s daily habits.

The pursuit of luck, abundance, and prosperity has always been an essential part of one’s overall wellbeing. The country’s predominant religion, Hinduism, is full of references to fortune, on par with many other spiritual principles found in scriptures and cultural traditions.

Naturally, because of the same diversity we emphasized above, the icons and symbols have a somewhat different significance by region/State, actual use, and historical period. It is also undeniable that some symbols are more inclusive in their adoption – such as the Swastika, going even far beyond national borders, for better or worse – others are unique for Hindu practitioners (and their less religious heirs), e.g., Aum.

We need to be able to analyze both larger and abstract ideas and smaller gestures and symbols, as their correlation and “togetherness” is the very essence of fortune, as understood by Indian culture. This collection of conceptual, spoken, and graphical representations allow for its symbolic significance to link – unconsciously for the locals – between layers of knowledge, awareness, and behavior.

From a popular “murti” (an idol or image of a Hindu deity or mortal) to its precise “mudra” (a ritual gesture or symbolic pose), one needs to be able to distinguish and appreciate a myriad of details. This(secondary) research piece aims to prepare a simplified schematic list of the essentials in symbolism related to luck and abundance.

While reduced in volume and depth, it should still suffice to give a glimpse into an average Indian’s mindset on the topic of lucky symbols and traditions. The subject matter carries implications beyond religious beliefs, state lines and ethnic customs and has influenced contemporary Indians in their lives, work, and favorite pastimes.

Religion Is Fundamental

Most of the auspicious essentials have their deep roots in religion. Naturally, Hinduism is the most relevant and important faith system in the land. Still, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Christianity (and others) have also contributed to the subject through the centuries to various degrees.

Almost inevitably, we should start with Lakshmi, the Goddess of prosperity and wealth. One of the most important deities, also known as Shri, is Vishnu’s wife and divine energy. Together with Parvati and Saraswati, she forms the Triad of great Goddesses (Tridevi).

Lakshmi is associated with fortune and wealth, even beauty and power. More than luck, she also stands for illusion and magic (“Maya”) and is associated with the main pursuits of human life – dharma, artha, kama, moksha.

Artha, notably, includes the pursuit of career and wealth, financial prosperity, and security. Therefore, Lakshmi is especially revered by those that seek abundance and a better turn of events.

Hindu symbolism views her as the essential Mother Goddess, the Supreme, and has given her over 70 names. Worshipers identify her in iconic representations by one of the main symbols traditionally associated with her – red lotus, a shower of gold, elephant, owl, a peacock feather, or a Kumbha (a piece of pottery intended as fertility and life).

Graphical tradition sees Lakshmi sitting or standing, almost always with a lotus. The mystical flower is a symbol of purity, above and beyond circumstances in which it has to grow (as it blooms both in clean and dirty water). Prosperity, therefore, can be found despite difficulties.

The elephants which accompany her (one or two usually) are known as Gajalakshmi. They stand for strength, work, water (rain), fertility, abundance, and prosperity. The occasional owl is a forewarning – refrain from greed (blindness) when wealth or knowledge has been attained.

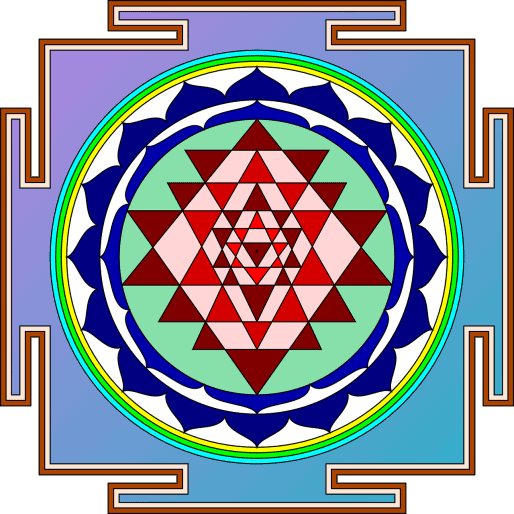

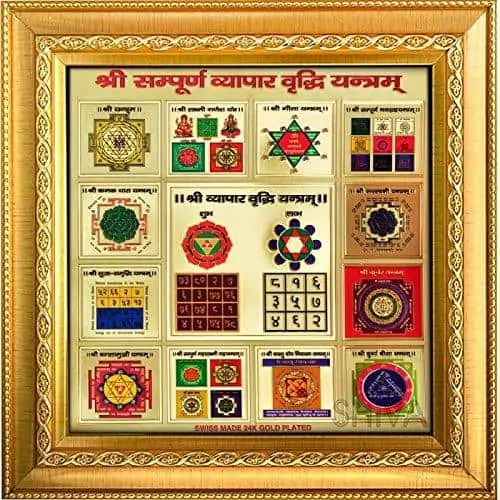

Shri (also Shree or Sri) is one of Lakshmi’s names. It is also an honorific term (meaning wealth, prosperity, and glory), as well as a yantra (mystical diagram, seen above) used to worship the Goddess of good fortune.

The importance of Lakshmi extends to her several known manifestations – the Ashtalakshmi, the Eight sources of wealth. While considered secondary appearances, the Ashtalakshmi helps to understand the Mother Goddess’s multiple dimensions. At least half of them are directly and explicitly related to luck and (material) abundance.

Adi Lakshmi helps believers achieve their goals, granting them the resources (wealth) they might need to do so. She is traditionally pictured with four hands, wearing gold jewelry and sitting on a pink lotus. The mudras (finger gestures) on two hands mean fearlessness and blessings, while the lotus and the flag held in the other two stands for enlightenment and righteousness (despite hardships) and surrendering to the divine, respectively.

Dhana Lakshmi translates literally as “wealth” Lakshmi, referring to monetary expressions of gold, property, or other tangible riches. Dhana Lakshmi is also associated with strength, courage, determination, and perseverance. Pictured with six hands, she has gold coins flowing from one palm, symbolizing the Universe’s wealth as an enabler for those who persevere in conquering the mind.

Vijaya Lakshmi (first name “Victory”) bestows success, teaching her acolytes hope and inspiration in the process. A positive attitude is what brings us to victory, in spiritual and any other sense.

The other manifestations of Lakshmi are also related to fortune and abundance, naturally. They include agricultural and animal wealth (Gaja Lakshmi is essential to farmers); fertility and parenthood (progeny); bravery and strength to overcome obstacles to spiritual and material prosperity; and intellectual abundance, meaning the wisdom and knowledge to be mentally resilient.

The Ashta Lakshmi is always worshipped and illustrated as a group in temples, households, and elsewhere.

The Eight manifestations of Lakshmi: luck, health, prosperity, progeny, fertility, strength, knowledge, and power.

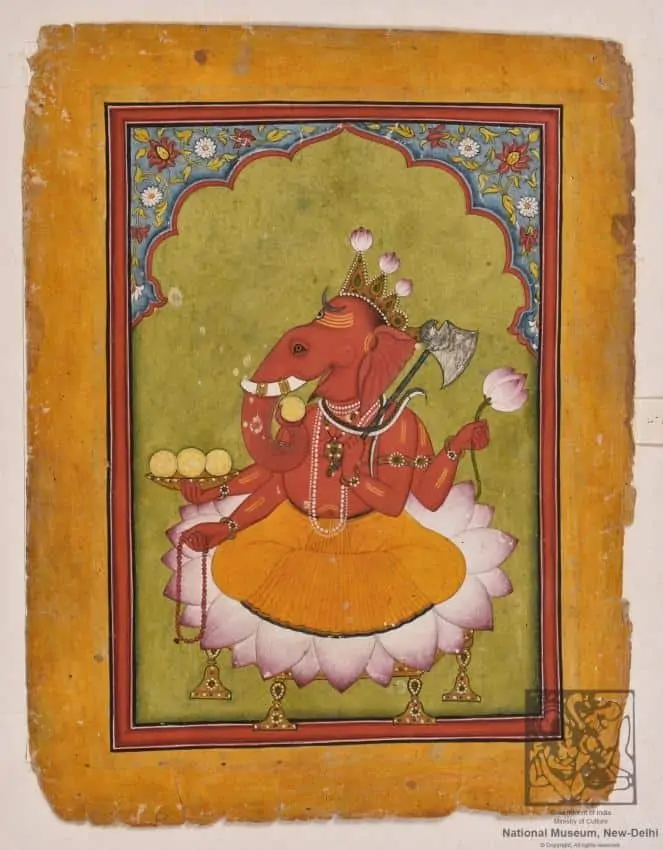

Ganesha is also a god revered for his influence on people’s luck. As one of the best-known Hindu deities and the son of Parvati and Shiva, he’s responsible for wisdom, foresight, and fortune. Also known as Ganapati or Vinayaka, he is the master of ceremonies and often the first to be invoked at a prayer (puja), letting in prosperity and fortunate new beginnings.

Also a “remover of obstacles,” Ganesha is celebrated well beyond India, around South-East Asia, and wherever there might be an ethnic Indian minority abroad. Domestically, even Buddhists and Jains consider him an important deity, again of success and good fortune.

Easily identified by an elephant head and a big belly, Ganesha has several arms (typically four). Elephants, as noted above, stand for strength and persistence, as well as water and fertility that ultimately bring abundance. Ganesha’s auxiliary symbols include the mouse (he might be riding it), a bullhook, a dumpling, and even Aum (see below, for wisdom).

There is another God of wealth in Hindu culture. Kuber (or Kubera/Kuvera) is the King God of the Indian “yakshas” (nature spirits). For many Indians, he is the true Lord of Wealth, leading devotees to financial prosperity and stability.

Kuber is traditionally imagined as short and stout (even dwarf-size), wearing jewels and carrying a club, along with a money bag. Other symbols include the lotus and the pomegranate.

Kuber has a sizable body of followers to this day, yet recent literature on Hindu mythology suggests that his place is mostly occupied by Ganesha, partly due to their association and functional overlapping. As a God of fortune and wisdom, Ganesha “overshadows him in the hearts” of most Hindus.

Similar to the eight manifestations of Lakshmi, there are eight important Auspicious Signs closely related to Hinduism (but also Buddhism and Jainism). The Ashtamangala includes “symbolic attributes” associated with numerous tantric deities and facilitates their teachings to mortals. These symbols stand for important spiritual qualities and are fixed ornaments of their iconic depiction.

At one point, there was an earlier set of auspicious symbols used during ceremonies and various celebrations. Intended for more solemn occasions, they included a throne, the Swastika, a hooked knot, a handprint, a vase of jewels, a pair of fish, a water flask, and a lidded bowl.

The present-day Ashtamangala includes:

A Jewelled Parasol (sunshade) – akin to a ritual canopy, signifies protection from harmful forces, illness, and bad luck. One may seek the auspices of dharma (universal truth, law) under the parasol.

A Conch Shell – considered a mystic symbol of eternity, it transcends the purely religious significance. Army leaders used to employ it for battle calls, while in Feng Shui, all shells stand for good luck.

A Treasure Vase – symbolizing longevity, health, prosperity, wealth, and wisdom, the vase reminds of Lakshmi’s Kumbha.

A Victory Banner – the flag initially stood for ancient Indian warfare, while the spiritual significance refers to Buddha’s victory over the obstacles to enlightenment. These are pride, desire, disturbing emotions, and the fear of death.

A Chakra – meaning a wheel. Traditionally, this would be a dharma chakra (i.e., the Wheel of Order/Truth/Law), representing the dharma teaching and the Buddha himself. However, it krishna smight also be a Sudarshana Chakra, the Wheel of Auspicious Vision. The latter should have 108 edges (lucky number, see below) and is used by Krishna (an avatar of Vishnu) as a weapon of protection. Indeed, the Chakras might even be substituted by a fly whip as one of the eight symbols, standing for the numerous Tantric manifestations of Ashtamangala. (The real-world version would be made of a yak’s tail and attached to a silver rod.)

Two Golden Fish – stand for the fortune of all animate beings that fearlessly persevere in the endless cycle of samsara (birth, suffering, death, and rebirth). There is no peril but success. The two fish also represent the sacred Indian rivers, Ganges and Yamuna.

An Endless Knot – an auspicious symbol altogether, includes several loops signifying love.

And finally, a Lotus – one of the main symbols of both Hinduism and Buddhism. As seen above (with Lakshmi), the lotus is a flower that stands for creation, beauty, purity, fertility, and surrender to the divine. Besides Lakshmi, the Lotus is associated with the Creator God himself (Brahma) and the Protector God (Vishnu). The lotus bloom might have a varying number of petals (e.g., in Buddhism, they are 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, 64, 100, or 1,000).

The Ashtamangala has somewhat different uses and variations according to context and religion, yet its repeated and unifying use emphasizes the importance of the iconic set. Used in a puja, wedding, or other solemn celebration, it preserves most of the decorative and symbolic meaning and cultural significance across Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Hinduism, in particular, presents variations with a lion, bull, serpent, necklace, pitcher, kettledrum, fan, lamp, mirror, drum, or an elephant ankus. Jainism may also include in its Ashtamangala variations a pitcher (or other similar vessels) or a mirror, but it might also have a chair or a hand fan. In other traditions, there would be a Swastika, a Srivatsa (a flower-shaped symbol), or a Nandavarta (a “mandala,” geometrical configuration).

The Ashtamangala is not an open-ended list of symbols and icons. Traditional representations depend on a region, time period, religious, and even social sub-groups. But all of the above are stably tied to the concept of auspicious meanings, fortune, and prosperity.

Another significant (self-standing) auspicious symbol is Om (or Aum). It’s considered fundamental for Hinduism, both as the sound of the Universe, the essence of mind, spirit, body, all in one. Whether depicted as a symbol or chanted as a mantra, Om represents enlightenment (nirvana) and collective consciousness.

Nowadays, Om is worn as a symbol by believers and non-believers alike outside of India, and the context of Hindu culture. As an amulet, lucky charm, or pendant, it is said to bring good luck and fortune to its possessors. Cultural appropriation is nothing new in Western society, but even India’s urban youth wear it as a fashion statement without putting too much thought into the original spiritual meaning.

One more familiar symbol standing for general auspiciousness is the Swastika. Revered since antiquity, it represents the overall distinctive spirit of Hindu culture.

The Swastika is right-facing, means “conducive to wellbeing,” and symbolizes prosperity, good luck, and the sun. On the other hand, the left-facing version of the symbol is Sauwastika and symbolizes the night and Kali – the demon-Goddess of time, darkness, and death. They are, therefore, not to be mistaken.

Both Hindus and Buddhists retain the Swastika as a holy symbol. One of the most important holidays – Diwali, the Festival of Lights – sees Swastikas frequently used as a household decoration across the nation. Workers, drivers, and many average Indians have it on them to keep away ill fortune.

Despite its current notoriety, the Swastika was a famous good-luck symbol around the globe until the early 1930s, as it had been for thousands of years in Asia. Largely in light of such popularity, the German National Socialist party adopted it as its signature symbol, albeit with some slight modifications (rotated at 45 degrees, never with dots, etc.). As a result, it ceased to be accepted as a sign of good fortune in Western culture but remained so in Asia to this day.

Chanting mantras is generally considered auspicious and helpful whether in a temple, at home, or before an important event. Almost a must for those looking for wealth, luck, and prosperity, mantras are directed to the respective deities, e.g., the Lakshmi Mantra (also known as the Money mantra). Mantras are said or chanted for a lucky number of repetitions – 11, 21, 51, or 108, in the case of the latter.

Between Religion and Superstition

There is a sizable – yet flexible to the eye of an outsider – group of concepts and practices that find certain justification in religious doctrines but are not formally defined within canonical literature or otherwise.

Some of these symbolic ideas and traditions have been mentioned in tantric or historical texts but have already evolved into another system of interpretations of their original meaning. Most of these concepts should not be depreciated as mere superstitions, especially since they are organized according to specific internal rules.

The pursuit of happiness is intrinsic to all humans as it is unceasing. Indians are also attempting and exploring ideas and behaviors that might make them feel more fortunate and blessed. Whether by trial and error or through tribal accord, cognitive patterns have led them to establish important (if peculiar) notions.

One of these is the practice of yagyas. Sacred Hindu texts have defined the above pursuits of all beings that are part of the Lord, his eternity, and knowledge. The Vedas assert the importance of happiness and advise the faithful to perform yagyas (or sacrifices) to maintain or achieve such a state.

The word Yagya is vaguely defined as a performance for the pleasure of Vishnu to get acknowledgment for one’s spiritual quest. Thus, a Yagya is a popular practice of worship or service to the Supreme Lord, without a sufficiently detailed description in sacred literature.

The two broad categories of yagyas are mentioned in the Vedas (mentioned in the Samhitas, the Brahmanas, the Aranyakas, and the Upanishads) and Puranas (a set of 18 mythological works written somewhat later), left largely to the individuals who choose to perform them. Some of these are to be practiced daily, others less often, on a special occasion, or even once in a lifetime.

Yagyas typically entail offerings to the gods, a fire as a centerpiece, and selected mantras to be repeated. Socially recognized (or self-proclaimed) spiritual leaders help the devotees choose these particulars, such as the wood to be burnt (mango, sandalwood, pipal, etc.) or the herbs and powders to throw in the fire. Naturally, the offerings are also crucial – e.g., grains, fruit, objects – and the time and place of the Yagya.

The fortunes that some believers invoke are more spiritual, personal, emotional. Others seek divine support in finding the right piece of land, acquiring property, or improving their material quality of life. In any case, all of the auspicious yagyas are considered very sensitive to timing, preparation, and disposition.

Vastu Shastra (or Vaastu sastra) translates as “science of architecture.” It’s a heterogeneous body of texts on traditional Indian design – interior, exterior, and structure – which reminds of the Feng Shui, more familiar in the West.

This ancient Indian geomancy has some well-established principles on ground preparation, structure layout and design, measurements, and space arrangement. Vastu Shastra covers the layout of residential buildings and gardens, towns and roads, shops, utility structures, and other public areas. To this day, it is considered beneficial, enabling its practitioners to align buildings, objects, and surrounding space to certain “magnetic axes” for “overall growth, peace, and happiness.”

The Vastu Shastra – along with lucky charms and various personal amulets – is hugely popular in contemporary India, seen around workplaces and households. Just as the Feng Shui, the Vastu Shastra is commonly followed to arrange personal, family, or workspace, including external additions like small idols, lucky stones, and much else.

Then there are the errors and defects of incorrect Vastu Shastra applications. When all the potential benefits are unattainable, and destiny is running in an undesired direction, it is said that some defects need to be eradicated, adding positive thinking and improved awareness about the entire geomancy system.

There are many Indians who have devoted their time and effort to establish a name as Vastu experts. Reportedly, they insist that Vastu Shastra faults cannot be corrected by mixing and matching (with) religious and other auspicious symbols. Precise and knowledgeable adjustments in buildings and surrounding space are said to be necessary to compensate for initial mistakes.

This brings our piece to a group of almost completely unrelated traditions, not grounded in religion yet justified by historical beliefs.

Tantra is the know-how of methodology in worshipping the deities via substances and materials. It is expected to help filter negative energy and vibrations and transform them into positive ones, thus attracting luck and prosperity. In reality, this rather informal field of study deals mostly with lucky charms, symbols, and objects used in Hindu mythology rather than religion.

Black Chirmi beads (rosary pea) are, for example, considered very auspicious. While the plant may be endemic to Asia, the black version of the bead is said to come from the Aravali mountain range and are believed to “find their proper owners.” The beads are supposed to have miraculous powers, never settling with an unlucky person.

The black Chirmi beads are symbols of Lakshmi and are, therefore, kept in purses, money boxes, wallets, and personal drawers to attract and keep fortune and wealth. Moreover, they are believed to repel the evil eye, physical hazards, and spiritual negativeness, as well as money-related problems.

Similarly, the Rudraksha is a tree seed used as a prayer bead in Hinduism, and other traditions. Its asserted benefits see it act as a protective guard against negative energy and misfortune.

The Sidh Swetark Ganesh is also a mystic plant, a root of a shrub named Ark. It is said to grow into a shape reminiscent of Ganesha, making it one of the popular lucky charms to carry around. The root is believed to attract Ganesha’s blessings to its owner. Further associated with Shiva, the shrub itself is known for improving concentration, wisdom, and family peace and harmony by chasing away negative vibrations and energy from the house.

One final enduring practice attempts to find its grounds in religious practices yet has little to do with any sacred literature or sensible belief system. The practice of baby tossing is a ritual that is still popular in certain parts of the Union. Infants up to the age of two are picked up by a priest, shaken, and then thrown or dropped from a 10 to 15 meter-tall shrine, temple, or mosque.

Essentially practiced in rural parts of India, the ritual is considered a celebration. This is yet another practice expected to bring good luck and long and healthy life to the child in question and their family, and prosperity for all the other participants present. Nowadays, men are holding a sheet for the baby to land safely, while initially, that was not the case (the Gods were expected to save them).

Astrology, Numerology and Stand-Alone Auspicious Symbols

It may seem a paradox that India is a country with a high literacy rate – compared to global averages – yet its population seems to place high confidence and faith in ancient rituals, bizarre traditions, and even pure superstitions, many beyond any possible rationalization. Expectations that symbolic practices and objects will bring luck and happiness are the norm for many Indians, and the sheer amount of such beliefs is overwhelming to the untrained mind.

The Yantras provide one such mystical representation of auspiciousness. Just as we saw one for Lakshmi, innumerable occult diagrams are used to worship deities in a temple, invoke their benevolence at home, or call for spiritual assistance when meditating. Yantras are supposed to bring benefits that emanate from their supernatural powers, largely based on astrology, sometimes on tantric literature.

Yantras are drawn, engraved, set within another object, framed, woven, or presented in any other respectable way, often placed in a position of prominence. Whether they are expected to bring luck, financial prosperity, health, or other personal and spiritual wellbeing, yantras are found everywhere and are treated as indispensable helpers to one’s life journey.

The Kirtimukha is a (head of a) monster, often seen on buildings and exterior arrangements. It has a gaping mouth and large teeth, symbolizing the “face of fame.” This strange idol is considered especially auspicious throughout India and around South-East Asia. It’s commonly fixed atop doorways and exterior walls of temples and houses, bringing luck and repels evil spirits.

Jewelry is also fundamental in desi understanding of auspicious symbols. Various gemstones are believed to bring fortune to whoever wears them, and usually, the shinier and more colorful, the better. Naturally, gems and jewels have to be selected according to their desired effect. Just as with some of the above informal beliefs, astrology defines the meaning and impact that these stones have on people.

Astrologers are called upon to study horoscopes, reveal good, potential, and existing obstacles, ultimately providing a shortlist or one specific type of compatible and auspicious gemstones. It is all very personal, and there are no universal effects traditionally declared.

Gemstones are said to represent and channel the Universe’s energy. Based on astrological attraction, jewelry with the right gems helps gain financial resources while bringing luck and prosperity to its owners.

Moreover, they have to be placed in the right position – the house or workplace, wallet, or cupboard. This helps them fulfill their potential and generate the expected fortunate effects.

Numbers

Hindu culture traditionally regards odd numbers as preferable to even ones. However, both 7 and 8 are especially auspicious. Seven is a lucky number in many of the world’s cultures (e.g., Seven Wonders, seven days, seven rainbow colors, etc.) On the other hand, eight is auspicious in neighboring China, standing for success and prosperity, and has a similar meaning in India.

A particularly lucky sequence of numbers is 786. Introduced and considered auspicious by Muslims, it stands for the total value of Arabic letters needed to write “Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim” (In the name of God, the Merciful, the Beneficent). However, 786 also stands for the Trimurti (Trinity) of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, as these are their respective related numbers in Hinduism. In more recent history, people have exchanged currency notes with the serial number containing 786 for exorbitant sums (tens of thousands of USD), giving the idea of how fortunate people think this may make them.

The number 108 is not only auspicious; it is also sacred in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. It is considered to provide a link to Universal truth and order (dharma) and is used as an honorific for gurus.

For Indians, 108 is the number of abundance, of completeness. A multiple of 9 (also considered “complete”), 108 represents the proper amount of repeats for lucky mantras, as well as the number of beads on a prayer string (mala).

Fruit

Fresh fruit is one of the traditional altar gifts for the gods, serving to attract positive energy – not only in Hindu tradition but also according to Feng Shui and Buddhism. Placed on the dining table, it also draws in abundance. Whenever fresh fruit is not available, people display paintings or art of fruit or even resembling decorative items.

The peach, in particular, is a fruit that symbolizes immortality (borrowed from Chinese philosophy). Peaches are also regularly associated with money and abundance, as well as health and long life.

Pomegranates are also very auspicious, especially for those looking for progeny and fertility. Lucky pomegranates are not always easy to come by, although they often ending up as display art.

Another red fruit adds to this symbolic power of attracting prosperity and abundance – the red apples, more common in the northernmost parts of the country.

Depending on their regional accessibility, pineapples, oranges, and grapes also stand for luck, wealth, and prosperity.

Plants

In this context, money-attracting plants sounds almost intuitive as a concept. Grown to bring financial benefits and “positive vibes” into a household or an office space, they are often combined with Vastu Shastra principles and other symbolic arrangements. The more popular among them include:

Ocimum tenuiflorum (Tulsi or Holy Basil) – Almost every household is said to cultivate the plant, even in urban settings. Native to the Subcontinent, it is held in high regard in Vastu Shastra texts, recommending an east or north positioning within the area in question. Holy basil is believed to bring wealth and health to the house.

Pachira aquatica (known as Money Tree) – Usually, several trunks are twisted and tied in a vertical braid. The Money Tree is expected to provoke the flow of wealth in the place. The end stems produce five leaves, also considered auspicious by Fend Shui.

Pilea peperomioides (Chinese money plant) – As the name suggests, this small evergreen plant is endemic in China with its distinctive round leaves. Feng Shui principles recommend placing the plant in a particular corner of the house to attract good luck and abundance.

Crassula ovata (Baby Jade Plant) – A succulent plant with thick and shiny leaves, usually jade-green (said to resemble coins). Business owners buy or receive it as a gift and a good luck charm. In residential buildings, it is kept near the entrance to usher in wealth and prosperity.

Epipremnum aureum (Devil’s Ivy or, again, Money plant) – Understood to bring good fortune to the house owners, both by Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui. The Devil’s ivy is a climber plant. This climber plant has leaves that resemble hearts and are known to purify the indoor air.

Ficus elastica (Rubber plant) – Both an indoor and outdoor ornamental Ficus, also regarded as a symbol of wealth and prosperity.

Chlorophytum comosum (Spider plant) – Easily recognized by thin striped leaves (green-white), the spider plant also invites good fortune in the home. Today, it is cultivated around the world as a household plant.

Dracaena sanderiana (Lucky bamboo) – Little could be added to the name. Wealth, abundance, and luck should come with it, according to pan-Asian customs. It’s recognized worldwide.

Cordyline fruticosa (Ti plant or miracle plant) – An evergreen plant, it adds a touch of color to the household (from red to orange to fuchsia). Indians try to grow it with only two stalks to gain luck, wealth, and even love.

Assorted and Odd Superstitions

As the above lists illustrate, customs, traditions, and habits add up to an immense body of beliefs in luck and abundance. The practically innumerable cases are sometimes only regional, unrelated to a national (let alone global) understanding of auspicious symbols. Others may still be inexplicable, pure superstition, but the result of cultural cross-pollination and possibly seen in other cultures, at least Asian ones.

The Indian belief system and superstitious nature share some notions that are seen around the world, including Western cultures – from the horseshoe being a powerful lucky charm (installed inside homes) to unfortunate events such as the breaking of a mirror or one’s path being crossed by a black cat.

Then there are some peculiar superstitions common to almost the entire Subcontinent. A prime example is the habit of eating a spoon of curd and sugar before going out, especially before an important event (that needs some extra luck). Urban or rural communities share this tradition, with matriarchs feeding family members with the spoon before stepping out. A rational explanation may be sought in the quick release of a limited amount of essential nutrients in the body. Yet, the superstition that this brings luck for the important upcoming task is beyond any reasoning.

The Dos and Don’ts of India’s Auspicious Beliefs and Practices

To this day, an important part of desi society is occupied by certain charismatic spiritual leaders. Depending on the state or ethnic/language group, they are known as baba, guru, shastri, swami, bhagat, bapu, or even godmen. They teach, interpret, assist and guide those who might need a hand in the maze of symbols, rituals, traditions, and superstitions. Almost all require some sort of payment for their services.

Just as some genuinely believe in the importance and responsibility of their role, others have revealed that this might have turned into a profitable profession without much of a systematic preparation or meaningful contribution for those seeking their assistance.

This regrettable phenomenon has created numerous victims over time and has repeatedly been addressed by various anti-superstition bills, especially in the past couple of decades. There was a national attempt in 2012 that never turned into a Law because of protests against it. The leader of the rationalist movement was even killed for promoting a campaign in support of the bill. There is only one existing Indian law against “objectionable advertisements” of drugs and magic remedies ever since 1954.

On a state level, Karnataka is a leader in passing targeted legislation against dangerous superstitious practices, starting in 1982 and, most recently, with the Karnataka Anti Superstition Bill of 2013. But Maharashtra is the State that has adopted the most comprehensive body of legislation against exploitation in the name of auspicious rituals and superstitions. The Anti-Superstition and Black Magic Act that has been passed in 2013 in Mumbai deals, however, mostly with “inhuman and evil practices” such as sacrifices, post-mortem (Aghori) rituals, and other serious anti-social and extreme practices.

State anti-superstition laws have not covered enough ground. India possibly needs a Central bill on the matter, focusing more on the victim and not the crime, more on the perpetrator’s benefits, and less on the customs that have led to the market for it. Cases of witch-hunting and human sacrifice are terrifying and need immediate attention, albeit being relatively rare.

On the other hand, there are serial examples of abuse of people’s beliefs and superstitions which lead to losses, distraught families, and individuals whose pursuit of hope and luck has ended up in economic and emotional impoverishment. The case is valid for purely religious motives, as it is for millions of Indians who see lottery and gambling as an investment.

Beyond legal considerations, there are the ethical or purely customary restraints that most Indians know and respect regarding their national symbolic traditions and iconography. One such example is the disrespectfulness of placing sacred Hindu symbols near or on top of private parts or the feet.

There is also the concept of sin, although not precisely as it is understood in Western tradition. Transgressions are often considered accidental, yet they still lead to remorse and might need some kind of atonement. But certain kinds of pāpa (or Adharma, not conducive to Dharma) are under one’s control. Greed is a prime example, and the inability to satisfy material urges (for things, money) is a clear obstacle to dharma.

The proper term for this “sin” is atyāhāra, eating more than needed, or collecting more things/money than required. Another aspect of this impure urge is the laulyaṁ, the greed for worldly achievements. Both kinds of uncontrolled urges are part of six transgressions that present obstacles to one’s devotion and spiritual growth.

In more pragmatic matters, it is considered advisable to avoid sweeping after sunset since Lakshmi – and luck, respectively – is believed to walk out of the house in such circumstances. The Mother Goddess is said to pay her visits after sunset and, should the household sweep after that time; she may not even come in.

Indians also believe in Alakshmi, the (not-Lakshmi) Goddess of misfortune. She is said to have a taste for sour and spicy food, therefore people – and business owners, particularly – tend to hang lemons and (seven) green chili peppers outside the door or place them near a burning lamp with some bright pigments nearby so that she could satisfy her hunger and not enter the premises. Otherwise, she might bring in bad luck with her.

Hindu culture also has the concept of the Evil Eye, and it is quite important. Superstition and prejudice about an evil eye that might potentially turn on someone is a cause for concern, and guides behavior, in some cases. The evil eye is understood to have the capacity to bring about substantial damages, both economically and spiritually.

As in other cultures, the evil eye is closely tied to jealousy of someone’s wellbeing or prosperity, with ensuing negative energy and vibes causing misfortune and incidents. Women (and babies, at the start of their lives) are seen wearing black kohl to ward off the evil eye, smeared on their eyes or forehead.

Hardly anyone in India might be upset when a crow, pigeon, or another bird poops on them. Bird droppings landing on one’s head or body are said to be rarer than the chances of winning the lottery (even though in dense urban contexts, that is clearly not the case). Thus, those who have had the messy honor of being pooped on by birds are encouraged to buy a lottery ticket since they are expected to receive money soon, one way or another.

What’s more, birds are said to represent the shadow planet Ketu, and their celestial powers might thus confirm that the “soul is heading in the right direction” and that sudden gain of wealth may be awaiting the lucky person who’s been pooped upon.

Naturally, when examined, many of these superstitions lead to a nonsensical explanation or a completely contrary effect, with bird poop especially illustrative as a carrier of parasites and infections. People feel that these practices will (most likely) not lead to any of the above effects. Yet, despite all that, they continue believing and behaving the way previous generations did, especially when it comes to innocent and superficial traditions linked to the pursuit of fortune and abundance.

Indians still avoid shaking their legs too much, as it is not a simple sign of boredom or anticipation but a representation of wealth flowing away from them. In some regions, leg shaking symbolizes kicking away the wisdom and knowledge already accumulated.

And they still avoid sleeping under or even going near a Peepal tree (known as a sacred fig) at night. The Ficus religiosa is endemic to India and is believed to attract ghosts that might kill those sleeping under it after dark.

Interpreting and transplanting such sensitive practices – emotionally charged, religious beliefs and symbolic traditions – out of their context can rarely produce satisfactory results. One particularly notable example is the iconic meaning of the Swastika. Historically, it was considered an accepted symbol of Nazi ideology for a decade or two, while it had been employed as a talisman of good fortune for millenia. Never a symbol of hate in Asia and India particularly, the “wellbeing” sign is universally accepted by Hindus, Buddhists, and Jainists, among others.

The fact of the matter is that in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the Swastika had also become well-established in Western culture as a good luck symbol, akin to a four-leaf clover or a horseshoe. But it remains a sensitive subject due to the global visibility of its negative links and will probably remain so for the foreseeable future.

Who Believes in Lucky Symbols

A demographic split of believers and practitioners of auspicious traditions and rituals is also quite challenging. The widespread acceptance of these symbols, on the other hand, provides the visibility needed to assemble a descriptive profile without simply claiming it’s everyone that adheres to these beliefs.

Reportedly, a higher percentage of females (~80 percent) might support and be “happy” with superstitious practices at home or the workplace, compared to their male counterparts (~68 percent). In a 2012 survey, India’s Tier-1 cities were observed through the participation of 800 companies operating there. The levels of superstition resulted highest in Bangalore and New Delhi, while the cities somewhat less affected were Ahmedabad and Pune. In any case, superstition and good luck charms were widely adopted across the nation. And it is quite difficult to trace a demographic profile of those who support them the most, especially given that the nation’s biggest metropolises have turned into melting pots of ethnic groups and religions.

Social Class

Some clear religious divisive lines apart, most of the main auspicious traditions are repeated nationwide. For example, the Ashta Lakshmi is worshiped by Sri Vaishnava and all other Hindu denominations and communities across India (although more intensively in the South). The Supreme Goddess in her Eight manifestations is said to find worshippers across all classes in India.

Class (or caste) divisions are fundamental in Hindu society, despite contemporary urges to question their rationalization and propagation. The Varnashrama dharma is understood to be a natural (not man-made) system, simplifying classifications of human labor and societal contribution. It is not seen as limiting but conducive to spiritual advancement.

The division of labor categories extends to aspects of social life as well. For example, in this context, those who perform business and commercial activity (the Vaishya or third-social order) have the responsibility and power of money. The Vaishya set aside a special day to worship Lakshmi, given her influence on money and abundance. During Diwali (or Deepavali), and especially on Lakshmi Puja (prayer day for Shri), wealthier cities see their Vaishya communities pile up silver coins and other valuables to honor the Goddess of Luck, above and beyond what other Hindus might do.

Other notable manifestations of caste-division worship are provided by the Shudras (the fourth class, laborers) who revere Lakshmi as the grain of other food they produce. The Brahmin (priests, teachers, or other spiritual intellectuals), on the other hand, are entrusted with the knowledge of the Mother Goddess, and they worship her as books. Practically all classes are touched by daily dependence on fortune and abundance and respect these traditions and rituals.

The lasting popularity and wide adoption of such practices is attributed to the “extraordinary religiosity” of most Indians. It did not enter into conflict with education or modernization; it has withstood these forces and has populated the same intellectual and spiritual space in their lives.

Thus, quite often, some of the most devoted followers belong to the Indian middle classes. They offer sizable donations (money, even jewels) to the deities in question, as do affluent Indians living abroad.

Sociologists attribute the rising flow of funds for religious and superstitious practices to the very growth in disposable income among the growing middle class. Other analysts warn that new realities and financial dimensions need to co-exist with old-fashioned values in a healthier (and possibly regulated) manner.

As mentioned in relation to legislative efforts, there are plenty of examples of unchecked growth and exploitation of people’s beliefs. The new generation of gurus has acquired skills, connections, and resources to influence mass media and achieve unprecedented visibility. Some daily TV programs have tens of millions of viewers and the topics addressed produce long-lasting effects in their mindsets and subsequent behavior. Hindu nationalist movements do not really help in this sense, as reiterated pride in traditions and values often brings any rationalist initiatives back to square one.

Current Scope and Daily Implications

The above steps provide a basic overview aiming to arrange, describe, and explain the symbolism behind the entire reference system addressing luck and abundance. Understanding the artistic, symbolic, and spiritual background from the past can help appreciate the allegory of present-day Indian iconography, both religious and secular. As mentioned, the unity of all these aspects provides a bonding factor, an element of togetherness between states, ethnic groups, and religious denominations.

Among readily apparent fortunate symbols in contemporary India, we often see lucky charms and protective amulets that are justified by religion and superstition. More importantly, these are not merely based on the Union’s indigenous traditions and culture. Popular global auspicious elements include the Turkish blue eye (evil eye) or the Chinese zodiac (animal) symbols.

Endemic or borrowed, fortunate elements are displayed at homes and workplaces, worn or carried around, included as parts of gifts, and passed on as an element of goodwill more than an immediate move to appease the deities. The concept of “making your own luck” is dominant and requires a proactive engagement on everyone’s part.

Some traditions and events are bigger than whatever an individual might be able to achieve. Regular or occasional festivities based on ethnic or religious traditions find their acceptance in interfaith celebrations across India.

As previously mentioned, Lakshmi is a prime example of a deity found beyond Hindu tradition. It is seen in Jain temples, while in Buddhism, she is also revered as the Goddess of fortune, prosperity, and abundance. Far-reaching also in a territorial sense, her attributes are similar in Tibet, Nepal, and large parts of South-East Asia, although often offered in an almost completely parallel representation by the Goddess Vasudhara. The latter (also known as Bhumi or Bhudevi) is more closely associated with earthly and tangible fortunes. At the same time, Lakshmi adds a more spiritual and personal wellbeing to the fortunes she brings.

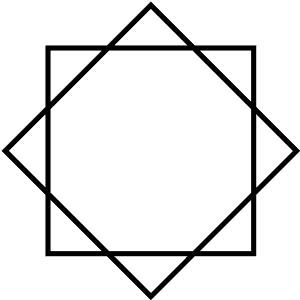

The significance of Lakshmi is sometimes simplified (i.e., narrated to children) as the one in command of the world’s wealth and power. The Star of Lakshmi, in turn, stands for these fundamental spheres of human life. But it is also reminiscent of the Eight kinds of wealth and the Ashta Lakshmi.

Closing the discussion on Swastika is its present-day usage throughout India. Put in plain sight on temples, businesses, and various buildings, including the Ahmedabad Stock Exchange and the Nepal Chamber of Commerce. The symbol is also common in Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and a frequent sight in Buddhist libraries. But it is the norm to evoke good fortune with it throughout India and Nepal, as even transport vehicles and people’s clothing have it on them. Weddings cannot go without a Swastika, and it’s included in numerous other Hindu ceremonies. We are reminded that the sauwastika (left-facing) is used in “darker” tantric rituals.

Swastik and Swastika (and other spelling variants) are people’s first names, male and female, respectively. The Government of Bihar employs two Swastikas on its State logo. Once again, when these symbols are placed out of their immediate fortunate context in Asia, they end up creating regrettable incidents and adverse public reactions, as was the recent case of online retailer Shein selling Swastika necklaces, even though it was possibly intended for Indians and other Asian buyers.

Festivities

Holidays and celebrations remain one of the most enduring modern representations of symbolism and auspicious rituals. Lakshmi is worshipped throughout the year, but it is on Diwali (or Deepavali), the Festival of Lights, that Hindus come together in a massive jubilant social occasion.

Diwali marks the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, enlightenment over ignorance, and hope over desperation, celebrated annually between October and November. Families dress up, light candles and lamps around and in their households, and hold family prayers. There is also a national Puja, followed by fireworks in most towns and communities.

It is arguably one of the major yearly festivals for Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and many Buddhists located in India. Quite importantly, Diwali comes with the habit and lasting tradition of gambling among family members and relatives, sometimes with friends for those far away from home.

The Lakshmi Puja is seen as a stand-alone religious festival in Hindu tradition. It falls on the third day of Diwali, conventionally on New Moon day, and is the period’s main festive day.

There is also a day dedicated to Gaja Lakshmi Puja, celebrated during the “harvest festival” (Sharad Purnima) in the fall – this time on Full Moon day. As the name suggests, the festival honors the “Lakshmi with elephants,” one of the principal aspects of Ashtalakshmi. It has established itself as an important feast of good luck, prosperity, and abundance. Also quite relevant to the nation’s habit of family gambling, during Gaja Lakshmi Puja, “card games are a particularly popular method of staying awake.”

Other Modern Interpretations of Fortunate and Misfortunate Customs

After centuries of well accepted traditions, many innovations and developments have flooded the Indian society. The majority have managed to co-exist with these customs, unlikely to change in a short time span. The “lucky” lotus remains India’s national flower, as the elephant remains the (informal) national heritage animal.

Indian corporate offices are not spared by superstition either. Well-educated and trained staff still consider traditional and supernatural beliefs a path to success and fortune. The above references to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui are valid and commonplace to this day in Tier-1 and Tier-2 urban workplaces.

The “Superstitions @ Workplace” survey measured personal faith in superstition at 62 percent, as more than half of respondents admit to bringing in superstition elements not only on their person but at the workplace as well. Preferred fortunate charms include the laughing Buddha, tortoises, frogs, and musical fountains, as well as the inevitable lucky bamboo shoots. Employers confirm that the overall acceptance of these beliefs and customs render it “non-conflictive,” compatible with modern lifestyles.

This is also true of present-day Indian gamers – they tend to have their favorite talismans, charms, crystals, or jewelry with them, whether going into the casino or playing online. On the other hand, they also observe some totally unrelated superstitions that are believed to determine your luck or the lack of it.

One must never shave on Tuesdays, wash their hair on Thursdays, cut it on Saturdays or trim their nails on Tuesdays and Saturdays. These are among the least justified by history, religion, or any other tradition as far as superstitions go. Yet, they are widespread, and almost every Indian believes they bring bad luck.

Similarly, most Indians agree that an itching palm is not just a superstition but an event influencing their financial situation. For women, an itching left palm means money is coming their way, while an itching right palm means they are likely to lose money. It is the opposite for men – an itch in the right palm brings money, and an itch in the left one suggests money will be lost.

Then, there’s the twitching eye. When females have a left eye that twitches, good fortune is on the way, an “unexpected windfall of luck.” A twitching right eye is inauspicious for them. Again, the opposite is true for men – a twitching right eye means luck; more precisely, they are likely to meet a loved one or their partner, or even an achievement of a long-held dream. When the left eye of a man twitches, it is “definitely” bad luck.

Some of the superstitions related to numbers we have seen were based on astrology and old-fashioned associations to deities. Others have turned into a habit without a clear foundation in the (recent) past. While this is not entirely true for the number “zero,” it is strange to see Indians avoid it at the end of monetary gifts, adding one rupee coin to the sum.

Shunya (śūnya), besides zero, translates into nothing, void, the end. Thus, on special occasions (i.e., weddings), people gift money ending on 1 instead of 0 (10001). This is considered thoughtful, a gift of a blessing, luck, and love, as you don’t want to wish a “zero” to friends and relatives.

The Influence of Evolution and Globalization

Human attempts to influence luck, prosperity, abundance, and wellbeing are often attributed to a lack of education or understanding of a more technical or scientific matter. However, as this has been the norm in India for centuries, we see millions of educated people and professionals around India with the same beliefs that some, even themselves, define as superstitions.

Indians may turn to a baba (or a tantrik) to solve their health, financial, or marital issues by using black magic and occult rituals. Some get recharged and turn more optimistic; others accept the situation and move on. Many others, however, fall victim to false advertisements and sensational claims, and these are often educated individuals, even the “elite of society.”

India’s rich history of superstition, mystical protectors, and divine auspices has shaped a general public that accepts and actively seeks such an outlook on life and the Universe. The acceleration of societal processes that globalization has brought has only given rise to the demand for quick fixes and easy solutions. Partly irrational thinking, partly a habit, these are promoted by word of mouth. Any success story and a lucky chance event result in people turning to old religious practices for an explanation, personal talismans for replication, or a new source of inspiration. Whether palm reading, numerology, astrology, or (tea leaf) prophecies, all are readily available in Indian society.

In present-day India, everything takes less time (and effort) to announce and become popular. The initial traditions took centuries to establish, teach, and get accepted. After India’s Independence, the united nation began looking at common inspiration fonts – one such example is the Ashtalakshmi Stotram, a devotional poem that became prominent in the 1970s, relatively quickly compared to previous sacred rituals. It is indicated as one of the actual reasons for the rise in Ashta Lakshmi practices since that period, with more home worship, temples, decorations than before.

Finally, with digitization, it is easy to see how a chance event, a prediction, or a bizarre occurrence may become viral and draw millions of new and existing believers. Sometimes it happens naturally; in other cases, gurus promote their abilities (on social media, usually) to “solve business problems, health, relationship, and future predictions” related to anything from the economy and cricket, to politics and celebrity lives.

Superstitions linked to fortune and mythology persist despite (and even because of) globalization and social media. Just like black cats go on bringing bad luck, mongooses continue granting fortune to those who spot them in the wild or simply because they went to the zoo. The global village merely accelerated, enlarged and empowered word-of-mouth.

One recent behavioral phenomenon proves once more that pursuing luck is in the very nature of desi people. Psychologists have compared the climate surrounding the booking of Covid vaccine appointments as the same feeling that gambling provides. Since the former are in short supply at the time of writing, people try their luck when booking an appointment via regular public channels.

For many, it feels the same as “gambling money in casinos or buying lottery tickets.” The news that someone was fortunate in their attempts is also given via social media, motivating others to keep trying. Vaccination centers release alerts and slot openings (also on social media) the way lottery numbers are given out. In this sense, many Indians have to pursue their luck and do so actively by placing that call, click, or message, just like a lottery ticket.

There are solid grounds in behavioral science for this trend. The incentive to take action needs to be based on a possible choice (and a limited supply). The feeling that people will have some degree of control is set apart from pure chance-based outcomes, even though the odds may be “stacked against winning an appointment.” Some have criticized this government approach, while others think that a healthy amount of gaming competition motivates society.

The game of Teer is just another contemporary example of linking desi gambling passion to the desire to actively evoke one’s luck. Punters are said to be able to train themselves to dream up useful indicators and symbols the night before a competition (e.g. an object or an animal) and interpret them as the winning numbers at the actual event.

Online Visibility

This analysis has already touched upon digitization and online trends (i.e., communication velocity and mass popularity). On the one hand, online communities and their messages are fragmented and multifaceted, just as societal reality is, both in India and in general. Everything may be found online, from the multitude of religious denominations and currents to pagan traditions and customs to pure superstition, and presenting it in an orderly fashion is beyond a person’s capacity.

However, on the other hand, there is a sense of pride around India’s rich history of religious and mystic traditions, especially since four major denominations emerged from these lands (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism). It is true that the majority of Indians identify as Hindus (~80%), yet the melting pot of ancient and contemporary traditions continually shapes and impacts societal norms.

Religion is more publicly visible in India than in most Western cultures. Sacred spaces and structures are everywhere, landscapes and locations are heavy with symbolic architecture, and even rivers are holy. More importantly, Muslims, Buddhists, and other religious groups find their place under the sun; their practices are commonplace, their temples often co-exist with Hindu culture and surroundings.

This translates into a motley cultural reality, visible both on the streets and online. With 750 million internet users (and rising), India is announcing, exhibiting, recreating, and commemorating its customs, festivals, and cultural practices in more ways than before, above and beyond what traditional media and television used to do for the nation’s cultural narrative.

Staying on the narrowly defined subject of auspicious iconography, there are innumerable web rings (even outside India), community networks, and societies looking for related news, mystic readings, fortune-tellers, and occult advice. While it is inconceivable to quantify and trace them, they are easily detectable and practically ubiquitous.

The same could be said about thousands of sites offering online sales of lucky charms, religious talismans, and astrological amulets. There are also entertainment channels, far easier to put up over streaming services and social media than through traditional media. All of the above influences accumulate content, influences supply (and even demand), raise the difficulty for searches and adds competition for online visibility on the subject.

And finally, yet quite importantly, comes the language factor that shapes online content. Reportedly, up to 90% of online users in India prefer searching and consuming content in their local language. If they search and post in their local vernacular, much remains under the radar for offshore digital operators and analysts. While English is the formal link between States, ethnic, and linguistic groups, it reveals a reality that tends to seem more globalized than it possibly is.

Despite that, it still discloses all the above interesting particulars and allows us to detect the main factors and trends that shape societal attitudes towards auspicious symbols in India.

Conclusive Remarks

For millennia, Indians have encoded their spirituality into a series of symbols, stories, and concepts, many of which address fortune and wellbeing. Traditions considered auspicious offer a sense of comfort and hope that luck and abundance will come one’s way if actively sought and correctly pursued. Making one’s own luck, in Indian culture, inevitably involves sacred objects, lucky amulets, words, and thoughts. And if that is not enough, one might seek support from spiritual leaders and, why not, an online community with the same beliefs.

Diverse customs, languages, and cultural practices all share a common social system founded on religion and tradition, historically and to this day. This is the essence of the cohesive force that unites 1.4 billion people.

The concept of mystical, auspicious, and sacred exceeds the boundaries of religion. Astrology, mythology, pagan art, architecture, and folklore provide additional dimensions that are a challenge for anyone who does not live India’s reality daily. Pure superstitions, too, cross not only state boundaries but travel around the world and find their way into desi homes, hearts and pockets.

The rich imagery of divinities is most likely the original reason the symbolism related to their following is revealed and practiced in so many ways. However, the active seeking of luck and abundance has spilled over into India’s daily habits, civic expressions, and even fashion. And it does not seem like any cultural interference or globalization trends may subdue it.