This report aims to take an in-depth look at Goa’s gambling communities. As one of the few states allowing gambling in India, Goa has an influence on gaming culture, tourism flows, and governance practices related to the sector.

The methodology used will be based mostly on secondary research sources and reports treating gambling in Goa, determining factors and spillover effects influencing both economy and society. Existing studies will be complemented by primary analytic data from ENV.Media properties. We will also cite publically available Government reports and state or national legislation to arrive at valid conclusions about Goa’s gambling industry and recommendations for its potentially beneficial development.

This approach will allow us to better understand a complex socio-economic phenomenon that has granted Goa and its gambling tradition a special status in India and abroad. This research will ultimately propose solutions to identified system shortcomings and approaches for facing current and future trends in the sector.

Historical Overview of Gambling in Goa

Indian gambling culture has always had a strong presence throughout the centuries. The earliest accounts come from ancient scriptures and legendary epic poems (e.g., Mahabharata and Rig Veda). An undisputed truth in literature and media reports, money games have been a favorite pastime across the Union, way before Colonial-time legislators outlawed most types.

Currently, States have the autonomy to hold horse races, run lotteries, rummy games, and grant casino licenses. The latter activity has historically been allowed in only three states: Goa, Sikkim, and Daman. In March 2021, Meghalaya also joined the group with their own Gambling Act but has not yet begun the actual licensing process.

However, desi’s love for real money games leaves room for a huge illegal market, mostly where regulated gambling is simply not accessible. Cricket betting moves the largest amounts, but Indians are said to bet on anything and everything. There are betting communities across the nation – and very little industry research on their existence, trends, and positive potential.

Unfortunately for all stakeholders, games of chance are only considered through the prism of legality. All subsequent effects are merely “observed” in the public discourse without any bottom-up argumentation. This does not allow for a coherent approach to gambling (be it on national or state level).

The primary objective of the 1867 Public Gaming Act was to prosecute “public gaming houses” – brick and mortar places for gambling. The Centre delegated discretionary powers to States to ultimately decide on the scope of gambling concessions and bans. The legal landscape was completed by the 1998 Lotteries Regulation Act and the 2000 IT Act. State-specific Amendments to these three Acts have made some forms of gambling legal for about half of the States/Territories (mostly lottery).

In reality, India’s passion for gambling is openly observed at festival fairs, with a rich choice of both legal and illegal gambling options. While gambling behind closed doors is a public secret, festival gambling is no secret at all, and no reasonable public official is expected to pursue or punish festival gambling.

The legal document which makes gambling openly possible in Goa is the 1976 Goa, Daman and Diu Public Gaming Act. Further notable steps include the 1992 initial release of gambling licenses to luxury hotels and the 1996 liberalization of table games (roulette or poker, e.g.), if only for cruise ship casinos. This last piece of regulation effectively made gambling operators in Goa seek an offshore presence, settling for the Mandovi river.

As the local gambling industry was growing in confidence, it also took a definitive direction towards mass markets – unlike Macao, which caters for high rollers. The chairman of Delta Corp revealed that the average player value is between $200 and $300. Only about a fifth of all visitors are “serious” players, hard-core gamblers, while roulette and blackjack are the most popular (and distinctly Western) games. Local casinos are competing exactly for those kinds of gamblers and gambling tourists who might have gone to Macao before the sector regulation but are happy to visit Goa for a more affordable experience.

Somewhat later (in 2006), the Lotteries Directorate in Goa set up a state lottery as a first meaningful way of promoting social welfare schemes – destined for poor, elderly, and underprivileged local citizens, including a special school. The change of “attitude” towards the role of gambling in society is the first sign that authorities realized a more sustainable approach is needed, with bigger social responsibility on behalf of those that profit from gambling in Goa.

Although slightly varying in numbers, there have been six offshore/floating casinos for the past decade and about a dozen land-based, primarily located within five-star hotels. The market leader is Delta Corp, the only Indian gambling company listed, operating the Deltin brand. Other relevant players include the Ashok Khetrapal fronted Pride Group and the Advani group (of hotels and casinos, led by its Pakistani-born founder). Interestingly enough, the latter operates in collaboration with Casinos Austria.

Although the first casinos in Goa opened in 1992, there have been no precise regulations and requirements for their daily operations beyond the licenses to do so for more than a quarter-century. Unrestrained, local casinos grew in importance and influence above other industries and even institutions in Goa.

Government officials have reportedly facilitated their expansion as well. Justifying and promoting their operation as the only way to attract sufficient tourist flow, casinos in Goa have been publicly backed as the State’s largest employers and tax contributors.

Tourism, in turn, has also been considered a second-hand revenue source – to the point of granting its gaming foundations the status of a primary industry that should not be questioned or reformed. Tourism and Chief Ministers in Goa have pointed to festival gambling (a.k.a. “zatra”) as pre-existing traditions that indicate the government’s formal and informal support for the big local operators.

Gradually, however, the same Government officials have become more sensitive to the social significance of the industry and the need for more precise regulations in the sector. However, instead of taking a leaf from innovative global practices, Goa’s public servants have opted for a more populist approach which is easy to sell but hard to justify with data.

As recently as 2019 and 2020, the Chief Minister has proposed to State legislators to adopt a ban for all locals to enter casinos. As of early 2021, the deadline for this was still to be set, even as the latest reports tell a story of “draft rules under study.”

Almost inevitably, the motion is set to fail whether the Government might admit it or not. The majority of casino visitors and related personnel are local Goans, making the solution essentially unsustainable. But the issue has become political, first and foremost.

Influence on Rest of India and Contemporary Gaming Culture

Goa is the smallest Indian state by area and has a population of around 1.5 million. The ability of its authorities to pass and implement regulations on such a small territory makes for a perfect case study dedicated to gambling laws, their efficiency, and spill-over effects.

More importantly, Goa may be taken as a reference point for a state which allows government-licensed lottery draws (like a dozen other states), as well as a state which has conceded casino games on its territory (three). Notably, lotteries are state-run, while casinos are always private.

This mindset follows the tacit Indian agreement that gambling, in general, is a “legitimate economic pursuit.” Whether legal or not, it has always been considered beyond its financial “opportunity” and beyond entertainment. Not surprisingly, in modern days, Macao and Vegas have served as inspirational examples, near and far.

India’s economic and technological growth in the past decade has coincided with the expansion of its gambling industry. Despite its obvious economic potential and ubiquitous social presence, the dominant legal framework poses more challenges than it offers solutions. Having cited the outdated laws that regulate the sector, it is no surprise that control mechanisms are not adequate – resulting in enormous losses due to illegal gaming, offshore/online operators, or simply because the majority of gamblers pay cash.

The popular Goa gambling scene suffers some of these shortcomings and influences other trends beyond its borders. Illegal operations are indeed less common in the state, given that sufficient gaming chances are offered within its small territory – and more are planned. But there is a growing number of local citizens who reach out to online operators, especially since Goans have been told repeatedly that they are not quite wanted inside the casinos of their own State. And cash gaming, certainly, has generated a grey area for operators to exploit, creating the feeling of fiscal obscurity and overall lack of social responsibility on behalf of Goa casino operators.

Failing to contribute to a better social balance and a more sustainable local growth (or even to adequately explain potential long-term positives of gambling presence in Goa), casinos and politicians who support them are often criticized by opposition parties, NGOs, and interest groups. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has held a few protest rallies in Panaji, Goa’s capital, pushing for casino closures and promising to do so if and when the AAP comes to power.

The main justification for such protests is not economic inefficiency, however. It is not pollution and congestion or any other collateral effect of Goa’s gambling industry. Opponents claim that the State economy should not be based on real-money games because it turns it into a “sin-tourism destination.”

What is more, Goa’s reputation might be a concern for more conservative (or populist) political or interest groups; essentially, it remains attractive in the eyes of a large part of the Indian population. This advances the same fears cited by gambling opponents, as they realize that, in fact, the Goa lifestyle – or the way it is portrayed externally – promotes gambling as a fun pastime and an exciting way to try your luck. For the rest of the country, an affordable glamour spot, a place where money games are legal, and people’s passions are welcome.

The fact of the matter is that Goa gambling operators and investors choose to go the way of more integration between casinos, entertainment centers, and inclusive tourism services. Family experiences and more diverse entertainment options are quoted as rising in demand, and after the nation manages to finally restart travel and leisure to pre-pandemic levels, Goa wants to be ready.

Last but not least, Goa’s influence on legislative practices around the country has not been as extensive as one might think. The two states that have casinos (out of the four that allow them formally) have remained an exception for India, and others have not followed with identical regulations.

Partly because some politicians and public officials have been aware of the questionable reputation and the shortcomings of the current regulatory system in Goa. Few proactive positions and solutions have been brought forward in the past few years, as public perception has gradually changed, yet remaining split in opposing directions. Some view gambling from a societal and psychological point of view, where gambling behavior needs understanding and possibly offering solutions to associated personal or group conditions (e.g., existing pathologies, accompanying social or individual problems, etc.)

And then there are those who view gambling mainly through the legal lens and wish to improve the legal framework which governs a potentially important industry for any State in the Union. As we saw so far, from a completely unchecked sector, Goa has moved into a reality where pressure groups and social responsibility remind State legislators that there is much to be improved in gambling regulations, control mechanisms, and innovative planning for upcoming economic and technological trends.

We need to wait and see what Meghalaya’s upcoming detailed legal guidelines might be. So far, the main Regulation of Gaming Act needs to be implemented in practice through various rules and procedures. This will be a first glimpse into what lessons other States might have learned from Goa’s gambling history so far.

Customer Acquisition and Profile

A prime example of such “lessons learned” would be the actual impact on tourism that gambling in Goa has had over the years. Stable demand for casinos makes them a key attraction for visitors from India, neighboring Asian countries, or even faraway guests looking for “exotic” thrills.

Gambling in Goa needs a physical presence, and the state can also offer splendid beaches and an all-night entertainment scene. The Government has shown its perennial support to the industry, despite some occasional declarations to the contrary. Tourism in Goa means gambling-related tourism.

Indeed, authorities have recently shown a preference for casino ships, granting new licenses only to companies planning offshore operations. Crucially, live tables and dealer-run games are usually found only offshore, with very few exceptions. But tolerating the existence of social side-effects has never prevented the collaboration between authorities and private gambling operators. Together, they have attracted Hollywood ambassadors to the cause and have strongly promoted the positive side of gambling as the root cause of Goa’s attractiveness.

Reports on the importance of the gambling industry as it exists today in Goa reveal some empirical economic conclusions: the State does not have sufficient high-end tourism appeal, and attempting to position it on such markets would not bring adequate benefits.

Such reasoning has made local operators surrender to the fact that many of their (desi) patrons might come with pre-existing personal and social shortcomings. However, they would be looking to get away in Goan casinos and surrender to an entertainment bubble. A 2019 study shows that Goa gambling communities have some particular socio-demographic traits which hardly come as a surprise: hardcore Goan gamblers report cases of “interpersonal violence, tobacco use, alcohol use and [even some] common mental disorder.”.

The numbers are eloquent in any case: 45.4% of all surveyed Goa residents have gambled in the past year, with lottery the most frequent form at 67.8%. In addition to alcohol and tobacco use (with a “splash” of violence), a strong correlation was also found to a rural residence. 50% of respondents admitted to having gambled at least once in their lifetime; hence those that have tried tend to repeat.

With age, Goans tend to play more lottery games. Interestingly, those that play Matka are also more likely to be smokers. Yet, since these personal traits have not been deduced as unconditional social determinants – the question is whether they are more a reason or a consequence of such gambling habits. A link between “lifetime gambling” and work-related problems was also established.

The above study also found that Matka (or Satta) had the highest frequency of all games played in Goa, with roughly 40% of players choosing the old-fashioned lottery from 1 to 3 times a week. We need to keep in mind that Satta Matka is still illegal in Goa (just like the rest of India), yet it accounts for a considerable amount of the black gambling market in the state. Matka is just as popular in other Indian states, e.g., Maharashtra.

Overall, 3/4 of all players practiced at least one game type, 1/3 did so with 2 or 3 games, while only 2.3% engaged in four or more. 45% of all Goa men identify as gamblers.

The above numbers have led to the commonsense conclusion amongst those that follow the industry that casinos in Goa are not that popular among locals. However, gambling resorts remain an important entertainment choice for all Goans, as confirmed by market shares below.

Locals are reported to outnumber tourists at land-based casinos (and media reports cite shares between 50% and 80% of all onshore casino visitors), and their weight in the market is precisely the reason why casinos in Goa would be hit hard if and when the ban on residents to enter is finally implemented. The several offshore casinos are the only ones that report over 70% of all players as tourists.

This has been an important change that has long been announced and often postponed. Rules banning the entry of Goans in gambling halls have seen some draft versions only recently, as confirmed by government officials. Several previous State administrations had suggested similar restrictions but stopped short of an actual implementation.

There is also a sensible reason for not having been able to go ahead with such rules. Legal experts remind that it would not only be unconstitutional but will also create a chain reaction of negative collateral trends – more corruption, the fabrication of fake IDs, and the sneaky entrance of Goans with more connections and political weight.

This is hardly what casino operators have had in mind for the past few years. Market leaders have promoted a common effort to get an “image makeover” – more family entertainment and less “vice pit” stigma. For that to happen, Goa casinos realize they need to pursue the universal appeal of Las Vegas.

Some have already gone ahead in pursuit of that family feel, with children’s daycare centers and a different tone in their ads and media messages. Delta Corp leads by example: it has introduced an entertainment program on its Mandovi-based ships (the Deltin Royale and the Deltin Jaqk), aiming to be more inclusive rather than narrowly tied to gambling. Music, stand-up shows, illusionists, and dancers are all part of it, as are kiddie games (without real money, of course).

Clearly, not allowing Goa citizens or permanent residents on their premises will destroy much of that image of inclusiveness that these operators are after.

Admittedly, those same Goa residents cannot agree on the role of casino tourism and its impacts on their state. Heterogeneous perception is reported, with “age, gender, income, education, and length of residence” all playing a part in shaping a person’s opinion.

One thing the majority agrees upon, in any event – the importance of tourism for Goa’s economy is undeniable, as it contributes roughly 30% of the State’s GDP. Leisure activities have dominated the entire sector since the infamous 1960s. And while the gambling industry might arguably be better run and regulated, it is that same segment that injected new life in Goa tourism since the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The Rise of Online Gambling

There is one type of gambling and casino development which is not able to promote tourism. And yet, it is growing in popularity on a global level. Online casino games in Goa have left their mark, just as they have across India.

There are many intersection points between the growth of online gaming and the current state of the Goa gambling industry. Gambling practices within local communities affect player acquisition but are increasingly influenced by the availability of remote gambling operators – often offshore, in the sense of foreign and faraway offshore.

Digital entertainment is increasingly popular in all of its shapes, and online (mobile) gaming has not been an exception in tech-savvy India and its well-developed state of Goa. Internet gaming has already nurtured a community of gamblers who tend to look for safe, legitimate, and regulated gaming platforms.

Primary ENV.Media data from the leading casino affiliate website in India, SevenJackpots.com, reveals some interesting trends when making national comparisons by State. The full research focuses on leading territories by user acquisition, conversion, and value, primarily when referenced to the mobile device and operating system type.

Given its size, Goa is somewhat further down such rankings. Yet, the data extracted puts the state in a position of greater proportional visibility in the online gambling market. Platform analytics include data from the first four months of 2021 and rank user visits and conversions from about 78 thousand users (via organic search only).

Goa users are responsible for an estimated 0.2% of all visits, provided that the state population is roughly 0.1% of India’s population. We must keep in mind that Goa boasts an economic development far superior to the nation’s average. Yet, reporting more visitors and successful user acquisition than all the North-Eastern States of Tripura, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh – combined – is impressive.

Although we are examining “only” tens of thousands of visits, Big Data rarely offers a deceptive curve – Goans know their games and are looking for online alternatives. (Incidentally, Meghalaya will be interesting to observe in the near future since it also decided to adopt a license-based regime for both land-based and online gambling forms).

If we are to confirm the above findings via secondary data, we need to establish a correlation to other legal gambling practices across India. However, most states do not allow online gambling, even if they do not explicitly outlaw it at present.

To scale up and comprehend the importance of mobile gambling through the Internet, we have already explored the “Key Reasons to Regulate the Gambling Market.” Tackling the current shortcomings of Goa’s gambling industry is the main proposition point. A more transparent, traceable, and innovative virtual gambling environment will have an important financial impact, helping fight money laundering and corruption. While it may be difficult to grasp at first, a regulated online gambling industry would have the technical means of promoting responsible gaming. It will also improve job creation and the business climate.

If these operations happen to be based within, accountable to, or regulated by Goa, the state will benefit additionally (and immensely) from its reputation and experience. Whether state legislators and industry stakeholders are ready and able to work together on such developments remains to be seen.

Effects on Local Development: Political, Economic, Social, Technological (PEST)

For a long time, albeit with different intensity through the years, the Government of Goa has been promoting casino tourism. Casinos were seen as necessary to uphold the desired economic growth, particularly after the State received its mining ban from courts. Iron ore mining had been a crucial driver of the Goan economy for some 50 years, until 2012. Additional bans and permit revisions in 2016 and 2018 finally halted operations completely.

Having to develop alternative means of generating public revenue, the Government pursued casino development more openly. This, however, was met with some protests, seeing that gambling establishments were expanding too rapidly and their importance became determining in many aspects across Goa.

Floating casinos “almost fused” with the capital landscape. Residents and politicians became aware that it is more important to plan ahead and face existing challenges in a structured way. Coming up with a sustainable strategy that maximizes gains yet counteracts negative collaterals is a meaningful alternative to protest messages calling for the return of Panjim to its pre-1990 state.

Goa’s gambling appeal has already put the State well on its way to becoming a casino capital of South Asia. The uncertain political climate in another nearby casino hub (Kathmandu in Nepal) and the unwritten demands of higher category gambling in Macao have facilitated Goa’s gambling operations. Yet, from hippy hangout to casino capital, the transition has not always been smooth.

Goa’s starting point has been that of an above-average economic development compared to the rest of India. Ranking high on most socio-economic parameters, the State reported 62% urban residents and an average literacy rate above 90%.

The expanding casino industry reached around 15,000 visitors per day by the end of the 2010s, still maintaining an annual growth rate of around 30%.

As for financial performance, Goa casinos had started slowly but confidently, with official revenue reported as low as USD 20 million in 2013, rising to more than USD 200 million a year later, with peak daily net profits at Rs 4.5 crore.

On the other hand, these numbers were still way below what has been cited as illegal betting turnovers, with cricket the market leader in that grey segment. Although hard to verify, research pieces have claimed (national) total figures that reach Rs 2500 crore for a single match (India vs. West Indies cricket) and Rs 30,000 crore per tournament (2016 T20 Cricket World Cup). The total annual Indian underground betting market was estimated in 2013 at Rs. 3,00,000 crores – more than USD 42 billion at 2013 rates – by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI).

While Goa is not physically able to accommodate unlimited gambling crowds, the potential for further growth is out there, especially if future plans include better digitization and online expansion for locally licensed operators.

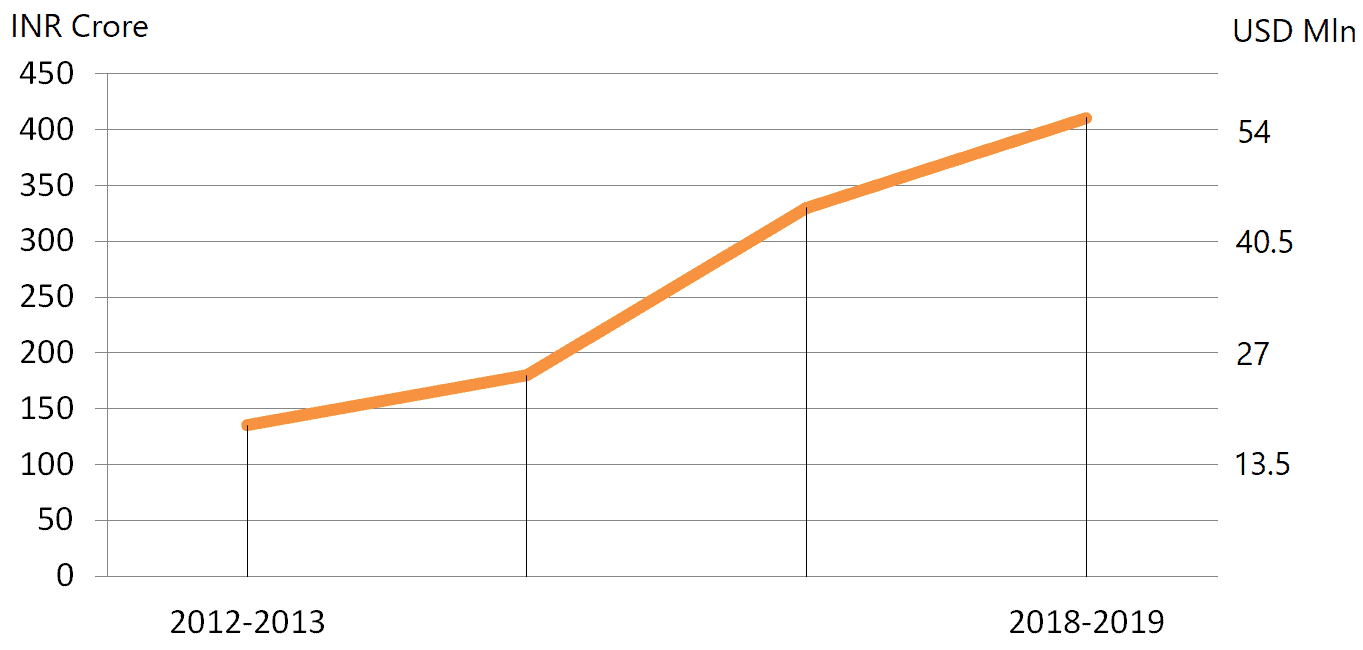

In comparison with similar fiscal periods, casinos in Goa have had a decent, if somewhat limited, impact on public tax revenues. For FY 2012-2013, they contributed Rs 135.45 crore to the government, including direct and entertainment taxes, entry fees, port charges, and liquor licenses. Media reports reveal that Goa charged Rs 6.5 crore per offshore and Rs 2.5 crore per land-based casino at the time. In total, ten land and six floating casinos employed about 5 thousand locals back then, only slightly lower than their present capacity.

The growth is there for everyone to notice, as in 2017-2018, Goa received Rs 330 crore (USD 45 million) from the casino industry, while a year later (FY 2018-2019,) the tax revenue was already Rs 414 crore, according to CM Pramod Sawant. 2019 was the last full pre-pandemic year before casinos were ordered to close, so these remain the highest numbers up to date.

The Growth of State Tax & License Revenues – Goa Gambling Industry

Naturally, tax revenue is only a fraction of the industry’s overall impact on Goa’s economy. Casinos heavily influence the labor market in the state, as they do in all countries and territories where they are allowed to operate. Even without sufficient solid proof for measurable effects on citizen earnings, casinos provide both direct employment and spillover earnings into surrounding communities.

The above report also highlights the increase in entrepreneurial activity and related business support that caters to gamblers. The “influx of wealth” is further measured by tourist overnight stays, second-hand entertainment spending, and even sightseeing related to an established destination like Goa.

In view of retaining more of such related positive spillover effects for the local economy, Members of the local Legislative Assembly asked in 2019 that 80% or all jobs in the casino industry be kept for Goa residents. Citing the need for better support for the local community – quantitatively and qualitatively – politicians remind that most of the workforce employed by Goa casinos still comes from North-Eastern Indian states.

Looking beyond the job market, the current Goan model might need some improvements in terms of overall governance and regulation. Still, the two states which operate physical casinos – Goa and Sikkim – are respectively 1st and 3rd in the national GDP per Capita ranking. In that order, the two territories have 1.5 million and 670 thousand inhabitants, and it is probably easier to influence their lives with a strong gambling industry. The fact of the matter is that more than one other state in the Union, officially or not, would like to be in their position of economic prosperity.

Current Trends

Despite the importance of the Goa casino industry – for the State and the country as a model – there has been little effort to conduct profound studies of the phenomenon. Apart from some financial and economic reports, there have been several research pieces available in the public domain.

Some of the research pieces include a psychiatrists’ account of gamblers’ exposure, attitudes, and awareness; an analysis of student gambling habits; and a similar study of student-age gambling-related behavior – all covering briefly important aspects such as public sentiment, social costs, proactive proposals by pressure groups and likely scenarios for future development of Goa’s gambling scene.

Moreover, effective and successful policymaking needs to be evidence-based. If the industry and its stakeholders have produced only passing considerations of cost-benefit analyses, there can be few sensible regulatory proposals and efficient solutions for moving the sector forward, including into the online dimension.

Much too often over the years, Goa Chief Ministers and other influential officials have said that gambling in Goa, as it is set up, is too powerful in both positive and negative ways. Citing “unhealthy” effects for tourism and society, frequently brought up concerns include “liquor, prostitution, and drugs.”

Promises to remove floating casinos from the river Mandovi have usually been followed by the realization of the important annual contributions that the state budgets receive from those same operators. While politicians often cater to emotions and populist urges, it is also true that casinos and gambling tourism operators have rarely – or possibly never – consulted Goa residents (interest groups, small businesses, let alone minorities or environmentalists).

Goan communities tend to agree that many jobs go to migrant labor and neglect local unemployed youth. While casinos are only a (disproportionally influential) sub-industry of tourism, many local residents are reported as wishing for a more socially responsible gambling industry, including better territorial links.

Goan aspirations have frequently been associated with successful practices in Macao as the “Monte Carlo of the Orient.” The tourism industry has openly discussed the social and economic impact of gambling, considering Macao a prime example with its over 150 years of gambling experience – including a period of state monopoly and the currently deregulated industry.

Common traits between Goa and Macao include exclusiveness – the former is one of the few places in India that allow casinos while the latter is the only one in China – and the importance of local communities’ attitudes in the planning and legislation process.

The transformation that Macao experienced when it made gambling more accessible is not the type that Goa might expect, as it departs from a different regulatory and business paradigm. Yet, the positives from Macao might serve policymakers as they shape strategies and legislation for the casinos of Goa’s future. Promoting economic growth while mitigating potential negative side effects requires plenty of concrete data, innovative thinking, and a higher level of social responsibility.

First in line with common fears comes the perception that residents would increase their gambling spending; pathological gambling would rise as an aftereffect, and crimes would abound if “immoral activities” surround the community.

Detailed Macao case studies show that residents are convinced by pragmatic evidence that they will not be involved in organized crime, social or political disgrace, or a series of vices as fallout from gambling presence on their territory. As anticipated, on the other hand, researchers highlight the economic development through tourism, tax revenues. Most importantly, with time, gambling has become a widely accepted leisure activity in Macao.

Casino operators in Macao have not only contributed an average of USD 3.7 billion annually over the past few years, but they have also done so with an increasing sense of social responsibility. Problem gambling is tacked through systematic programs and regular donations to those who need it – individually and collectively. When the industry makes an effort to give back to the community, it makes it even more acceptable in the public’s eyes, considering the common problem of government tax money not reaching them in a desired way and proportion.

As things currently stand in Goa, the main concern of local communities is reportedly the rapid and unsustainable expansion since the early stages of the local gambling sector. Safety nets have not been established, and imposing restrictions at this point becomes a sensitive issue for all stakeholders, often irrational or difficult to impose.

CM Pramod Sawant announced in early 2020 that the Government plans – again – to stop “original” Goans from entering casinos. In the eyes of locals and public officials, visitors from India and abroad see a completely different Goa, not the unpleasant community which has essential support functions to an expanding casino-based industry. Put simply, for some; this is a pastime and entertainment. For others, it is the daily life in support of an industry that has become bigger than many state institutions.

Despite such popular notions – as discussed above – a ban on Goa residents will be both discriminatory and nearly impossible to impose as imagined.

A more significant change has also been touted for several years – removing floating casinos from the Mandovi river, possibly sending them out to sea for overnight trips with less frequent visitor intake. The proposed measure met another delay in early 2021, with the new deadline in October. This gave casino ships another six months to operate under the current regime, while the Government will need the time to elaborate more precise instructions and regulation mechanisms. Covid-induced holdups were officially given as the reason for the delay.

Social Costs

The latter concern – “ruining the Mandovi landscape” – is long-standing and quite prominent among Goa’s infamous gambling collateral. This includes ecological impacts and congestion, primarily. The two aspects are closely related. River traffic volumes have been constantly higher since the existence of floating casinos. Ensuing environmental problems are easy to trace against permitted ecological limits and acceptable standards.

Studies by the National Institute of Oceanography (between 2002 and 2007) and the Goa State Pollution Control Board (2014–2015) have revealed extremely high coliform levels and other bacteria, making the water essentially unsafe for consumption, bathing, and even water sports. Claims by the Goa authorities that casino vessels respect current ecological regulations implicitly transfers the responsibility onto those same public institutions which failed to build better water purification infrastructure or impose more stringent waste disposal requirements.

Another leading concern of Goa resident communities is the potentially unquantified rise in crime because of the questionable reputation that gambling tends to have. The prevalent assumption is that there is indeed a link between casinos and crime. However, crime rates have not increased for the past few years; they have even decreased. Between 2014 and 2017, the CM noted in front of legislators, crime counts had dropped consistently and had no apparent relation to casino operations.

The same 2018 sectoral study we cited above reveals that citizens specifically worry about drug trafficking, theft, prostitution, and money laundering – all potential signs of organized crime presence. However, general tracking in identical settings has revealed that such links are inconclusive at least. The Macao case study even brought scholars to the conclusion that there has been an overall decline in organized crime manifestations.

The reasons for this trend are to be found in the market pressure that important casino operators exercise locally, leading to improved performance by the administration and better gaming process management that manage to prevent criminal infiltration in most cases.

A final but crucial public concern in Goa addresses mental health status, with problem gaming and related addictions as leading examples. While local studies have barely explored the subject (except for the two inquiries mentioned above), more has been done in other former Asian colonies with rich gambling traditions.

A 2015 study registered a slight increase of problem gamblers in Macao, from 4.3% in 2003 (13,666 people) to about 6% in 2007 (24,162). This covers the years immediately after the administration opened up the casino industry to foreign investors following decades of a stiff monopoly.

However, similar transition periods in Singapore and Hong Kong never indicate the slightest rising in problem gaming in the aftermath. Quite the contrary, according to the Institute for the Study of Commercial Gaming (ibid). Hong Kong registered a decrease in problem gamblers from 5.9% to 4.5% (between 2001 and 2008), while Singapore went down from 4.4% to 2.9% (between 2004 and 2008).

When industry studies and legislative efforts consider these social costs and citizen concerns, they cannot reasonably claim that these efforts are unfounded. However, both existing good practices and diligent preparatory work for efficient regulation hold plenty of levers for countering negative social costs and reaping the evident benefits of a well-functioning gambling ecosystem.

Drawing from Experience: Possible Solutions and Recommendations for the Goa Casino Scene

The above studies and datasets provide evidence for several social benefits: increased personal and group income; stable financial flows into the public domain; investment into infrastructure and facilities; better recreation and tourist visibility.

Almost inevitably, there are the above concerns or social costs associated with the gambling industry. However, some pragmatic solutions have already been successfully implemented and might serve as lessons for Goa authorities.

Surplus budget income might be designated to larger-scale public spending on environmental protection (as imposed by Macao’s Environmental Protection Services Directorate in 2006). Specific investment levels might also be required towards urban development, social security, education, tourism, and charity (again, exemplified by the Macao government regulations). These sums are earmarked apart from regular taxes and concession fees.

Much of the traffic, pollution, and crime concerns could be alleviated if an increased portion of gaming activities is transitioned towards online operations. While such an approach might impact tourist flows directly related to physical gambling tables, many of these shortcomings are precisely and proportionately caused by such dependence.

Extending licensed operations into a legitimate virtual gambling dimension will give access to more players from India and abroad and will maintain and increase the positive economic benefits to Goa residents and public finances.

While an increasing number of Asian countries have accepted gaming as a revenue driver, Goa tourism might initially suffer its liberation from a direct link with the gambling industry. However, in the mid- and long-run, it is likely to shift towards a more independent functioning, with gambling as a support activity and not a main driver.

Digitization can promote other proven good practices in the field. Potentially negative effects are easier to control through safeguards and automated mechanisms. These are also more easily monitored by a casino controlling body. The latter is possibly one of the first steps to take for the Goa government. A dedicated Regulator Authority and a professional sector administration will greatly improve the efficiency and public-private coordination.

Ultimately, isolating and moving a number of game operations online will hide many of the negative “externalities” and their visibility to the public.

Other successful examples of gambling regulation (including digitization) come from the Scandinavian countries and the UK. Recent research on Gambling review and reform (carried out by the UK Gambling Commission board in collaboration with NGOs) indicates that it is much easier to regulate and implement safety mechanisms when operating online.

Particular measures that are successfully implemented include content access limitations which serve as a mitigating instrument against potential harm. Targeted towards vulnerable players, these mechanisms detect harmful play modes and are triggered against them.

The underlying principle is the establishment of an Index of harm. An entire legislation category is based on this rationale and is used for content accessibility even outside gambling contexts. The UK Parliament has passed a gambling deregulation bill (in 2013) which shows that establishing such an Index of harm with proportional mitigation mechanisms is the least intrusive and costly way of achieving public protection. UK legislators have planned for competition, innovation, and growth while ensuring consumer and public safety.

The Goa gambling industry should benefit from strategic recommendations that help minimize the negative impacts on local communities – through on-site regulation mechanisms, digitization, and online content transition. The fact of the matter is, in Sweden, Denmark, the UK, and other well-regulated markets, all the trends that are perceived or proven to be negative have become less aggressive with time.

The Future of Gambling in Goa – Back to Basics or Looking Ahead?

In mid-2020 Goa Tourism Minister affirmed that the State Government plan is to “bring back the 1960s,” this time by welcoming wealthy tourists only. Calling it an effort to reinvent and return to the kind of tourist destination Goa was 60 years ago, the Minister was hoping to strike a chord with more conservative or nostalgic Goans and those who have no links to the current tourism industry.

The twist comes with an open preference “against budget and local tourists.” Moral considerations aside, this is in no way an evidence-based method for making Goa more beautiful or less crowded. And it resonates as a paradox, to say the least, since the hippie community put Goa on the international tourist map back in the 1960s. The State’s popularity has peaked in the past two decades, largely because of more liberal casino licenses. And if the stigma and collateral problems are too evident or difficult to fix, erasing decades of development hardly sounds like a more sustainable approach.

Having spoken of the repeated efforts to move the ships out of the river (and cease issuing new permits for floating casinos,) this initiative seems destined to happen sooner or later. Reforming the land/river policy framework is something that merits expert legislative attention. However, the Government simply seems to never have tried enough so far.

Thinking along different lines, in 2019, the Goa Authorities approved a motion to set up casinos at the new (then proposed) international airport in North Goa. The Chief Minister revealed to lawmakers that these integrated complexes would have casinos, hotels, and numerous other facilities. The CM also ruled out the possibility of relocating existing river casinos to the same area. The last important update from an early 2021 session was that the creation of a Gambling Commissioner’s office was finally under study.

A couple of months earlier, Delta Corp had already received regulatory approval to set up similar integrated resorts in Goa. The gambling giant announced that Goa’s Investment Promotion and Facilitation Board had sanctioned in principle a complex with hotels, a convention center, cinemas, a retail area, a casino, and a water park in Pernem (near the new MOPA Airport).

Apparently, this new planned, detached and integrated approach to hosting gambling-related tourism is expected to help diversify the leisure and tourism package and promote infrastructure and tourism away from mainstream casino establishments. Analysts expect that this will be the way forward for land-based integrated gambling according to Government plans for the near future at least.

In fact, this change of concept does little to optimize regulations or tackle existing system defects. But at least it pursues how Singapore has already developed its gambling industry, and its success (with all the conditional factors) is not in any doubt.

Singapore managed to change local beliefs resisting gambling developments by building highly integrated resorts which simply contained casino sections. These projects improved both financial results and limited local exposure to any potential collateral fallout. However, Singapore authorities carried out massive public consultation campaigns via “letters, emails, polls, and other forms of dialogue designed” to assess public sentiment. The resulting approach exploited economic benefits and tried to limit social negatives in a closed ecosystem.

Ultimately, Goa casinos are still legal and will remain in sight in one shape or another. They still have considerable appeal for the growing Indian middle class, pulling the tourist boom, which will inevitably come back after India and the World manages to fight back the pandemic.

The bold attractiveness of its flashy side will continue to define the gambling industry. However, any plans for future developments will, inevitably, need to present more sustainable elements and consider Goa society as fundamentals to build upon and not just voiceless bystanders.

Financial and Economic Potential of Goa’s Gambling Industry

At the end of the day, any substantial investments and legislative initiatives that address gambling communities in Goa will need to have a sound economic and financial justification to go ahead.

Currently (or at least before the spring of 2020), the local gaming industry was annually drawing over three million tourists who brought precious external funds to the state. No matter which side of a discussion a Goan stands, they will hope to keep these revenue levels and even increase them.

Since 2012, the Government has reported casino contributions of almost Rs 1300 crore to the state budget. Offshore casinos tend to bring in almost twice as much as land-based ones (again, because of external cash flows from those 70% of tourists aboard).

We need to consider the last full financial year (FY19 with its Rs 411 crore revenue, as detailed earlier) to grasp the starting base of operations. However, other media reports cite calculations by opposing politicians who speak of over Rs 4,000 crore per year of lost revenue (~USD 0.5 billion) due to various leaks – including undocumented cash payments as a major fault. Put simply, the revenue potential for the State of Goa might be up to 10 times higher than what it has been lately.

In comparison, the US State of Pennsylvania might be more advanced economically, yet it is not anywhere near the international popularity of Goa as a gambling destination. Despite that – and having legalized casinos merely 15 years ago – Pennsylvania brings in the second-highest gaming revenue in the USA, behind only Nevada (with Las Vegas). Casinos and race tracks attract visitors from surrounding states and generate USD 2.5 billion in taxes for the local authorities, with over 33 thousand jobs supported (2018 data the last fully available). The total economic impact is reported at around USD 6.3 billion.

As much purchasing power as East Coast Americans might have, Pennsylvania still does not reach levels that Macao manages to reproduce year after year. This comparison proves that commercial gaming policy depends on surrounding conditions (infrastructure, supporting industries, etc.) but may rise above and beyond them in a matter of several years. We are reminded that Macao and Goa are both former Portuguese colonies and have started from a similar overall development level.

University of Nevada research explains that after its restoration to the Chinese Government in 1999, Macao (a Special Administrative Region, SAR) was working on its repositioning as a top-level tourism spot precisely by pushing liberal gaming and opening up to foreign operators (since 2002). The latter brought in the competitive edge and modernized both entrepreneurial culture and facilities. More than just symbolically, in 2006, Macao surpassed Las Vegas as the world’s largest gambling center.

The Macao Business board reported more than USD 23.5 billion in gaming revenues for 2010, a 58% increase on the previous year. More relevantly, the Gross National Product breakdown shows that casinos had an 11 percent share in 2001, rising to 80 percent in 2014. Admittedly, however, Macao cannot be an identically replicated business model for Goa, as we already emphasized its high-roller clients with particular tastes. VIP baccarat, for example, generates around 70% of total casino revenues across given years.

Goa, on the other hand, relies on a few large operators targeting the mass market. The Deltin Royale is a prime example, with up to 1000 physical gaming positions. However, should the state gambling industry wish to grow (sustainably), private operators and the Government should be open to alternative business models and platforms.

One particular paradigm shift would be the already suggested online operations. Practically unlimited in their capacity, they are safe against prolonged force majeure situations such as the recent pandemic concerns. Many of the “Key Reasons to Regulate a Gambling Market” are even more relevant with online casinos in mind.

Should more Indian companies and gaming operators be able to register and operate under Goan laws, they would increase manifold the economic impact and tax revenues that the segment can bring to the State and National public coffers.

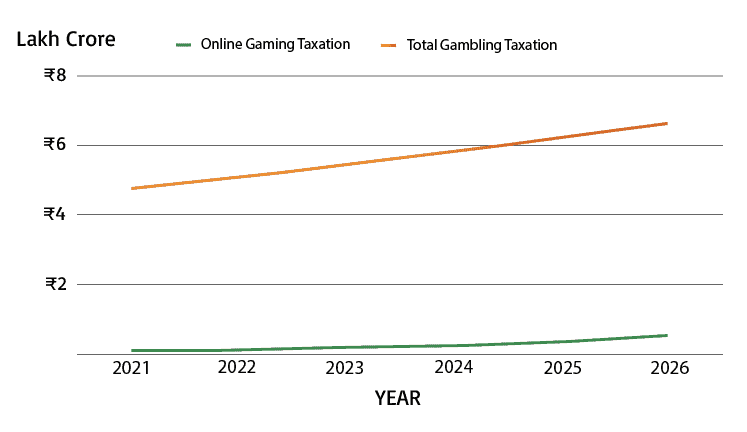

When considering taxation and financial efficiency, numbers speak louder than any political statement. A 2019 KPMG report estimated the Indian betting market at $130 billion (₹9,50,000 crore) and in continuous growth for the past decade. The huge potential of India’s currently unregulated national markets is also re-evaluated more recently by the 2021 Deloitte India report. The latter cited online gaming alone as worth $2.8 billion (₹20,500 crores). Even though a much more contained amount, online games are growing rapidly by around 40% annually at this point and already represent 10% of the Union’s Media and Entertainment economy. The segment, again, is impenetrable to many of the global crises and indeed was shot into financial orbit by the stay-home urban culture as of late.

According to most taxation laws in India, about half of a company’s total turnover might end up as taxes. Based on the market size quoted above, online game operators would contribute around ₹53,000 crores in annual taxes by 2025-2026 (should they maintain current growth). Taxing the entire gambling sector in the country might bring in up to ₹6,60,000 crore in the same year, but that is currently not a manageable task for the entire Government, let alone a State.

Estimating taxation revenues from a regulated Indian gaming sector. Source: SevenJackpots.com

In any case, as many or as few of the country’s online gaming operators – and even foreign casino platforms – that Goa might be able to attract to operate under its jurisdiction, we are considering financial results which dwarf any tax collected by Central or State authorities at present. (And we are not including annual licensing fees and other charges).

Instead, Goa hotels and casinos are stuck waiting for news and a green light for the full reopening of the industry. Previous Unlock stages did not include them and greatly affected the industry in current financial results and collective preparation efforts.

The legendary status and huge success of famous casino centers like Monte Carlo, Las Vegas, or Macao have inspired locals and Goa authorities to allow old-fashioned gambling operations for the most part. Naturally, these have paid off and brought economic development opportunities to the State. However, it is time for the local Government to look ahead and try to attract different player profiles, scope outside markets, and reach out to virtual gambling communities.

Psycho-social research we repeatedly quoted above has shown that legal gambling has a market-shaping appeal, much more than gambling in illegal settings might ever do. The growth of legal online/offshore casinos has established economic dimensions which were simply not there a decade ago.

Most recently, Meghalaya became only the fourth State to regulate gambling under a license-based regime. However, Nagaland is not actively exploiting its regulatory regime, and the states which benefit the most are currently only two – Goa and Sikkim. As per the recent ordinance, the license-based regime would be applicable for both ‘games of skills’ and ‘games of chance,’ and licenses will only be granted to “Indian citizens or companies incorporated in India” (to be renewed every five years).

This definition leaves open the opportunity for almost any operator to gain the legal right to run an online gambling platform under Meghalaya jurisdiction (as suggested above for Goa).

Whether Meghalaya and its newly established Gaming Commission will be able to capitalize on this opportunity remains to be seen. However, they have the opportunity to copy good practices, implement automation and digitization standards, and run and monitor all gaming activities easily, both in and out of the State.

On the other hand, the well-trodden path of offshore casinos has appeared attractive to other States in the Union as soon as the Fall of 2020. The Andhra Pradesh government was reportedly exploring the possibility of licensing floating casinos within its territorial waters, off the coasts of its largest city, Visakhapatnam. Raising resources and creating local jobs the way Goa has done seems attractive enough to the AP authorities, who are said to have spoken to the Centre about it.

The State debt, insufficient revenues, and the possibility to link gambling to its tourist exposure (along the capital beaches) caused the AP Government to consider the move. It is said to explore lottery draws as well.

Quite interestingly – and not too long ago – Andhra Pradesh banned online gambling explicitly and became one of only three states to do so. Therefore, the State government is likely hoping to physically attract tourists to its new casinos without considering the fact that allowing one channel and cutting another will simply produce fewer taxes and spill-over economic growth while limiting other such opportunities.

Conclusions. Further Implications for Online Gaming Verticals.

Gambling licenses and tax revenues are often considered textbook examples of additional financial flows – for example, when the local economy is not growing or producing sufficiently and when fuel, tobacco, or liquor taxes are already at their maximum tolerable levels.

When gambling operations run into their structural limits or significant territorial difficulties, nowadays, it is possible to move most activities online, concede licenses to faraway operators and further exploit innovative business models.

The State of Goa is currently still heavily dependent on tourism, whether in combination with gambling or not. One possible solution to get over this dependence is to move towards online and virtual casino operations, starting afresh in some regulatory aspects and “leaving behind” others which create more concerns than benefits.

Taking a step back is not feasible since nostalgic ideas overlook the fact that before the casinos, Goa was a “drug-infested hippie heaven.” The gambling industry is what brought prosperity to the State, and it has the potential to do it again.

On the other hand, industry studies suggest that more training can be given to residents who wish to be part of casino tourism. This will extend current benefits, provide more employment opportunities, improve the quality of life of more Goans and encourage better infrastructure facilities. However, the industry will probably need to restructure and rethink its land- and water-based casino establishments and the current regulatory regime.

Further comparative sector analysis suggests that the Goa government can, and should, use media for awareness campaigns to better inform and educate gamblers. Casinos themselves should be stimulated with flexible incentives to get some meaningful territorial visibility through social responsibility efforts and support to potential or current problem gamblers.

The Government, in turn, must be more transparent about its debts, plans, and responsibilities towards citizens and vulnerable groups. Should casino revenues be used (partly) for education and social welfare schemes, the end-use could better justify the means in the eyes of Goans.

However, if Goa’s authorities decide to issue new casino licenses, they should probably not clutter the scene additionally. Catering more to online gaming platforms and dedicating upcoming concessions to online casino operations will grow local revenues while avoiding more local problems.

The Covid-19 pandemic may have given the decisive push in many industries. While tourism stands to improve in Goa, its gambling fame might just be brought onto a new level with online gambling. Goa might push for more online gamers and next-gen revenue streams instead of pushing for rich tourists (and trying to discriminate against locals or humble desi gamblers).